Chronic pain patient Grace* says marginalised growers, including those who identify as LGBTQ+, are facing exclusion from both the legacy and legal cannabis communities – and have more to lose by speaking out.

“I’m really proud of what I grow, and I want to be able to share it,” says Grace, 42.

“But as someone who is already quite marginalised and on the edges of society as a disabled, queer, trans person, I feel more vulnerable to retaliation.”

A former garden designer, Grace has been growing cannabis at home for several years, mostly for their own medicinal use but occasionally providing friends, family and neighbours with oil to ease their anxiety and aches and pains.

Grace lives with multiple diagnoses and debilitating symptoms of their own, including chronic regional pain syndrome (CRPS) – thought to be the most painful condition known to the medical profession.

“I’m in my 40s now and I’ve had chronic pain my whole life,” they say.

“I can’t remember a time when my body wasn’t in pain.”

From their late teens, Grace felt they weren’t taken seriously by medical professionals and sought out drugs to help them cope with the pain. After battling dependencies on heroin and crack cocaine for two decades, a major health scare – which they almost didn’t survive – was the catalyst to them getting free from heroin.

“That was the moment that I stopped because it scared me so much,” Grace says.

“I didn’t want to take any drugs at all once I was sober, but as I reduced the opioids I was struggling more and more with the pain. The doctors tried antidepressants and referred me to physio and a pain clinic, but it got to the point where there wasn’t much they could do.”

Discovering cannabis as a medicine

Grace tried CBD first, before buying whole-plant cannabis flower from the street.

“I remember being very anxious at first about taking it, in case it triggered any addictive tendencies,” they recall.

“But then realising that it had quite a profound impact on my pain levels, whereas none of the traditional medications I had tried had.”

Despite claims by its critics that cannabis is a ‘gateway drug’, leading consumers on to harder substances, Grace has found the opposite to be true.

“I don’t think cannabis is a gateway drug,” they say.

“I think there’s more and more evidence proving that it’s actually an exit drug for a lot of people who have had addictions in the past, even with things like alcohol.

“It doesn’t trigger any of those feelings of dependency. Once you have reached a level that you like, you don’t really need to go any higher than that. There isn’t a hangover, there isn’t withdrawal like with heroin, where you develop a physical dependency and it can become a lifestyle.”

They add: “It means I can function; I wouldn’t be able to walk my dog without it.”

Growing their own

After Grace saw the benefits that cannabis had on their quality of life, their background in horticulture meant learning to grow their own was a natural progression.

“I didn’t have a clue what I was doing, but it just takes practice,” they say.

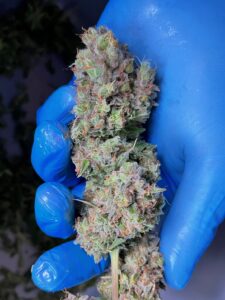

“I think the horticulture background definitely helped. I’m an organic grower and I spend a lot of time researching. The quality of my cannabis compared to even some of the best available on prescription, there is no comparison.”

Grace had a legal prescription for cannabis for six months before it became unaffordable. They explain: “I was trying to keep a prescription to stay legal, but it’s just unaffordable for me. Some suppliers are better than others, but in the end, I was paying street prices and it was such poor quality.”

Growing is not only medicinal for both Grace’s physical and mental health, it’s become a hobby and something which they would like to earn a living from one day.

“It can be hard work for someone with chronic pain, but it’s great because it’s a hobby I can do from home and mostly on my own. It allows me to manage my health conditions, and I could even support myself financially eventually,” they say.

“It’s frustrating because I would love to build a business out of this and actually work my way out of poverty, but I’m not allowed to do that.”

Giving legacy growers a seat at the table

In the shift towards more liberal cannabis laws across Europe, some jurisdictions have adopted regulations that allow patients and caregivers to grow their own medicine. In Malta, people are permitted to grow up to four plants, while draft proposals for the legalisation of adult-use cannabis in Germany include allowing consumers to grow up to three plants at home.

In the UK, a petition launched last year to allow patients to grow their own medicine gathered almost 3,000 signatures, but otherwise the ‘home grow’ movement has remained largely underground.

Grace is concerned that, as the legal medicinal cannabis market expands, individual growers, and the wealth of knowledge and skill they have developed over years of cultivating, will be left behind.

They would like to see a cannabis caregiver model introduced in the UK, similar to that in states such as Michigan, where patients and carers can apply for a licence to grow a certain number of plants for medicinal use.

“As patients and medical growers, we’re concerned about our place at the table,” they say.

“Where is the equity going to be between the people that can afford to invest millions of pounds and those who haven’t got two pennies to rub together but want to help other people who would benefit from the medicine but can’t afford it or are too scared to try it.”

They add: “Medical legacy growers really need to be included in the conversations from the get-go.”

Divisions in the cannabis community

But it’s not only the legal industry which they feel excluded from. Grace has seen transphobia, sexism and racism within the legacy cannabis community.

“You expect people to be open-minded, but I’ve experienced disgusting comments from people within the weed community,” they say.

“I’ve had to prove myself in order to be accepted by some of the legacy growers. It’s similar to what many female growers experience, and that’s why I’m trying to talk about marginalised growers a little bit more.”

Grace believes that many marginalised growers feel unable to speak out about the discrimination they have experienced out of fear of not only criminalisation and legal repercussions, but also of the hate they might receive online.

“A lot of people don’t want to go public, because it leaves them open to not only the risk of prosecution but also personal attack,” they add.

“I’m an activist at heart so I want to fight this battle, but you are constantly thinking about the risks.”

LGBTQ+ and the cannabis industry in context

The relationship between cannabis and the LGBTQ+ community is a historic one.

LGBTQ+ campaigners played a fundamental role in the fight for access to medicinal cannabis in the US during the AIDS crisis of the 80s and 90s, yet many were thrown in jail or ostracised.

There is little data on LGBTQ+ representation in the legal cannabis industry today, even in the US where the markets are more established. However, according to industry analysts at Vangst, representation is double that of the general US population, putting it way ahead of the traditional corporate world (although this doesn’t take into account generational differences).

Last year, US-based luxury retailer Farnsworth Fine Cannabis founded the Queer Cannabis Club, the first consortium of LGTBQ+ owned and operated businesses in the cannabis industry.

However, many would argue there is still a need for more LGBTQ+ individuals to be given a platform to share their experiences, and for wider industry recognition of the role the community played in changing the narrative around cannabis.

Read more about the LGBTQ+ activists who fought for access to medicinal cannabis here

*Grace’s name has been changed to protect their identity.

- CBD anal lube is now a thing – here’s everything you need to know

- Six online CBD communities you should join

- Charlotte Figi tribute concert raises $250k in her memory

- RCK launches first catalogue of cannabis strains “suitable for every disease”

- Field of dreams: the CEO of British Cannabis

on building a legacy

on building a legacy

The post “As an LGBTQ+ grower, I’ve had to prove myself in the cannabis community” appeared first on Cannabis Health News.