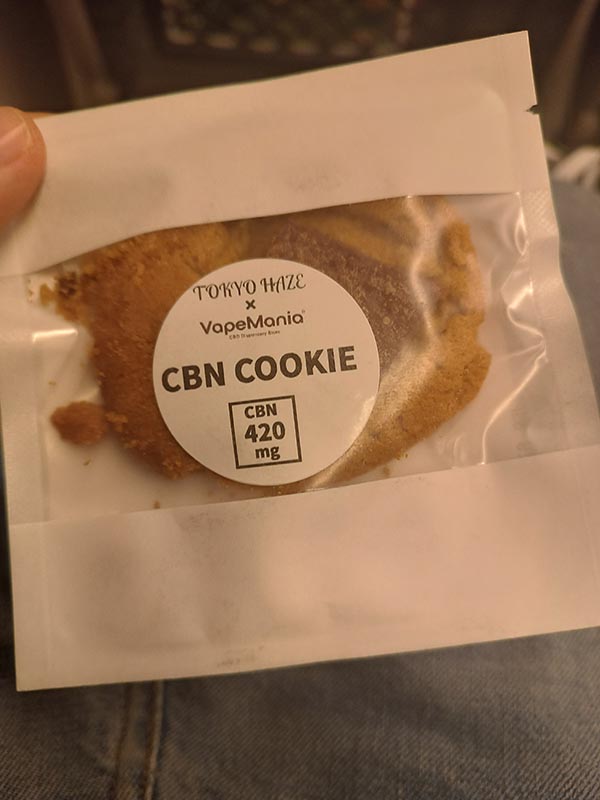

A glass bong filled with fake, green, chocolate buds sits on the windowsill of a dispensary in Ueno, central Tokyo, stocked with every kind of cannabinoid goodies imaginable – there are wax dabs from England, CBD gummies, CBN cookies, and even pet treats.

“Maybe 10% of Japanese people know what CBD is – there are few stoners in Japan, but now it’s becoming more popular,” said Aki, whose shop VapeMania, which he opened in 2017, was the first of its kind in Asia.

“Our main customers are for medical use, some businessmen, and middle-aged mothers. But the current regulation doesn’t even allow advertising for CBD and very few famous people use it, so there’s very few opportunities for people to learn what CBD is.”

Over the past several years CBD-based products have been making inroads in Japan thanks to a loophole allowing cannabis products made from stems and stalks to be imported to Japan as long as they contain no THC. They’re even available from Don Quixote, one of Japan’s leading discount chains. There’s a perfect market for it: a rich, ageing population hoping to stay healthy.

But Aki has to be careful with what he stocks and keeps his inventory clear of anything potentially psychoactive. In Japan, while the government’s relaxing on the groovy herb being used for medical purposes, it’s tightening the screws on anything that might get you high.

While many parts of the world are now easing up about a little greenery, Japan’s still holding fast. Which is a little odd, considering the plant’s position in Shintoism, the national religion. Priests wave bundles of leaves to exorcise evil spirits, and until the early 20th century, cannabis (taima)-based remedies for aches, pains and insomnia were commonly found at pharmacies.

But during the American occupation after World War II, taima was outlawed under the 1948 Cannabis Control Act, and later, in the 1980s, America pressured Japan to toughen its laws further still as part of Ronald Reagan’s War on Drugs. But while the Americans might have imported the war on weed, the Japanese would fully embrace reefer madness. An intense propaganda campaign convinced the public that taking drugs is a sign of weakness, poor self-control and bad character.

The government doesn’t even care if you’re dying of cancer. In December 2015, a French chef named Masumitsu Yamamoto was picked up for possession.

“He didn’t buy weed from the black market, he bought seeds and grew them in his bathroom,” recalled Hideo Nagayoshi, a journalist who supported Yamamoto when he decided to take the government to court and fight back, challenging the law on cannabis.

“He was walking with weed and he was questioned by the police and then he was caught. And then he was put into pre-trial detention. And so he stayed there for 20 days, but he had cancer. So while he was there, his condition deteriorated and when his trial began, he had to go to the courtroom from the hospital.”

Yamamoto died of advanced liver cancer eight months later while awaiting the verdict.

“That case got reported on TV, and there were many people who first learned about this concept of medical cannabis because of that case,” said Miki Naoko, from the legalisation lobbyists Green Zone. “So it was a pretty big deal. But then he was waiting for the decision and died, so we don’t know what would have happened.”

Naoko and a young doctor, Yuji Masataka, set up Green Zone in 2017. Naoko, a translator by trade, first got interested in medical marijuana after working on a book by American author Peter McWilliams.

“After I translated his book – which had nothing to do with cannabis, it was more like a self-help book – I tried to contact him because I had some questions, and found he had died a few years before,” she told me.

“After medical cannabis became legal in California, he was using it as a patient because he had AIDS. But he was an author, and he was a well-known figure. So the federal government arrested him to make him a scapegoat, and basically released him on the condition that he will not use cannabis at home. So as a result, he died choking on his own vomit in his home. But I thought it was ridiculous. I mean, it was cold murder by the government. And it really was. So I got angry. And that sort of stuck in my head.”

Together with Dr Masataka, Miki introduces Japanese physicians to experts such as Ethan Russo, screens films such as Netflix’s Weed the People, and advocates on patients’ behalf.

In terms of marijuana laws, Japan’s even behind some of its neighbours, although not by much. Thailand was the first country in the notoriously strict Far East to allow medicinal ganja in 2018, shortly joined by South Korea.

“We went to see a clinic in Thailand where they would practise medical weed, and there were a lot of Japanese patients there,” said Nagayoshi. “And of course, some people have severe illnesses like cancer and are in pain, and then there were also people who had depression or couldn’t sleep at night who are experiencing benefits at that clinic. And then when they come back to Japan, it’s not available.”

At the moment, the only way to get hold of mary jane, for therapeutic purposes or otherwise, is illegally. According to Nagayoshi, there exists a small, secret network of patients sharing the medicine.

“Compared to outside Japan, the [medical marijuana] community is very small, but it does exist, these networks,” he explained. “They acquire the seeds and then grow the weed, so it’s not usually imported from abroad. And these networks are person-to-person, so they’ll have a tight relationship with one another and then they would distribute weed, maybe for free or at a really reasonable low price.”

However, homegrown chronic may not be precisely what the doctor ordered.

“When you think about the CBD as a regular medical option, the quality control is very very important,” said Dr Ichiro Takumi. “So I don’t want patients to have something from the black market which might be poisonous.”

Takumi is a member of the Japanese Clinical Association of Cannabinoids (JCAC), which is currently running a series of clinical trials to treat severe forms of epilepsy and tuberous sclerosis. Based on the outcome of these trials, he’s optimistic that cannabis-based medication, in the form of a liquid spray, will be available in just a few years.

“We have a very strict cannabis law in this country – we can’t prescribe medicine as doctors, and we can’t receive the prescription as patients, if the medicine is derived from cannabis,” he told me at his office in the brain surgery wing of the St Marianna University School of Medicine in Kawasaki. “But something like a clinical trial basis is not at all written in the Act.”

We have a very strict cannabis law in this country – we can’t prescribe medicine as doctors, and we can’t receive the prescription as patients, if the medicine is derived from cannabis,

Dr Takumi learned about the healing potential of cannabis by conversing with fellow epilepsy experts from Britain and America.

“There was a giant in the field of epilepsy study in the UK, Martin Brodie, who came to Japan,” he remembered. “I had a talk with that gentleman and he said to me, ‘you know what? A hundred years ago, we said 70% of epilepsy patients can be cured by cannabis.’ I was very shocked to learn that this gentleman from the UK knew from his history that cannabis works for epilepsy. We found from books and thesis from the 19th century that medical cannabis works for the patients with epilepsy, already written in the 19th century!”

While only a handful of test subjects can access the medicine now, Takumi is confident that his colleagues will be able to prescribe cannabis-based cures in the next three years. But – and this is a crucial point – this is not the same as medical cannabis itself i.e. those sticky green buds labelled Afghan Kush or Skywalker OG.

The Japanese ministry of health is currently planning to lift the ban on cannabis-derived medicines, providing the trials prove they are safe and effective. But at the same time, with the number of youngsters caught with dime bags climbing year-on-year, they’re planning to ban smoking weed. That is, while having a doobie in your pocket is a dishonourable felony, actually being high is not. The law was written in such a way as to protect hemp farmers should they “accidentally” ingest intoxicating elements (30 or so farmers are still licensed to grow hemp for Shinto rituals and the like).

So, one step forward but two steps back?

“Right now, if you smoked it and it was within your body, they can’t challenge you,” said Rose, who reviews cannabinoids and CBD products on YouTube, “but we are concerned how are they gonna check and catch people with THC in their system.”

“Of course, foreigners are also coming to Japan, so how will they know if foreigners smoked weed in Japan or their home country?” added Yoda, CEO of a CBD import business. “Same thing for Japanese tourists, because we can go into the West Coast of the US, smoke weed, then come back.”

“The government will reform the law this year, and one of the things they’re trying to do is legalise it for medicinal purposes, so things are looking better now,” said Hideo Nagayoshi. “[But] they are also trying to criminalise being high, and that’s not respecting people’s human rights.”

But Miki thinks that attitudes are slowly changing.

“I think among young people, attitudes are already changing because they’re more internet-literate,” she explained. “But the police are overreacting to that and they’re still sending out messages that sound like they’re from the Reefer Madness era. I think what’s important to change people’s minds is normalisation. So my hope is that by focusing on medical cannabis as a normal, middle-aged woman like me, and not being afraid to talk about it, that’s how we’re going to win the hearts of my generation that’s so afraid.”

Meanwhile, as I type this, the CBN gummies I had from Aki’s dispensary are kicking in. I’m not sure if it’s a placebo effect and I’m already tired (I haven’t slept for 18 hours) but I’m feeling relaxed, like I’d blazed half a zoot. I can feel myself drifting into a peaceful snooze so I flick off the lights in my little hotel capsule pod. Not entirely un-psychoactive, after all.